How Postholer Went Serverless Using Cloud-Native Geospatial Data

Meet Scott Parks, a trailblazer in the world of map development who is transforming hiking experiences through geospatial data. As the founder of Postholer, a resource for hikers that features interactive trail maps, Scott leverages open-source geospatial tools to provide hikers with smart mapping solutions.

Our team first became aware of Scott’s work when he built upon Kyle Barron’s demonstrations of how to create responsive browser-based tools to work with large volumes of geospatial data. Scott believes that cloud-native data has enormous potential in the way we present data, particularly spatial, on the web.

In this interview, we learn about Scott’s journey into the cloud-native geospatial world and gain insights into how new approaches to sharing data on the Internet have allowed him to make data more accessible to hikers.

Your work at Postholer has resulted in an array of trail maps, including interactive maps, elevation profiles and snow conditions. What inspired you to create these diverse maps, and how do they cater to the specific needs of hikers and outdoor enthusiasts?

While planning my first hike of the Pacific Crest Trail in 2002, I realized the lack of standard answers to frequently asked questions, such as, “How much near trail snow is currently in the sierra?” or “How cold does it get at location X in June?” Having a passion for the outdoors (public lands) and technology, I attempted to answer some of these questions.

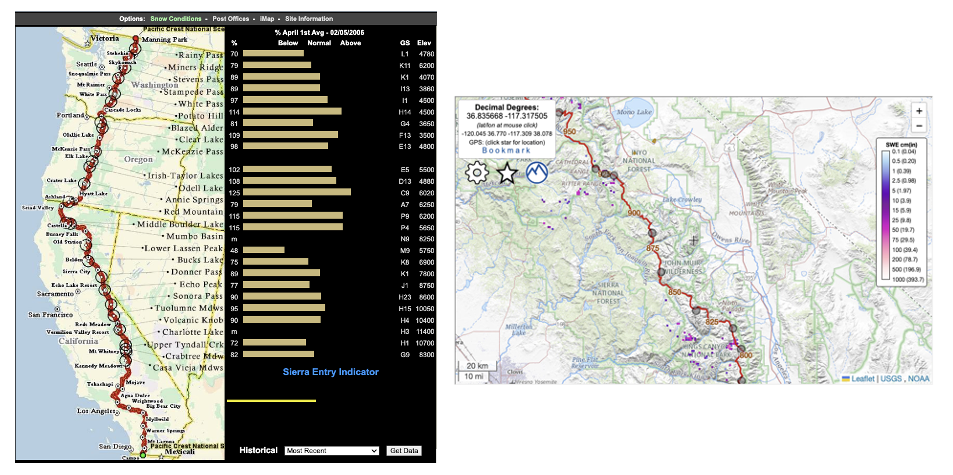

In 2003, I introduced the embarrassingly general sierra snow graphic using data from CDEC and SnoTEL. Ironically, 2003 was the first year the Snow Data Assimilation System (SNODAS) was modeled, which eventually became my go-to source for snow data. That beginning led to the addition of climate, weather, wildfires, fauna and other data over the next 20 years (and counting).

Comparison of the Pacific Crest Trail Snow Conditions Maps: 2006 (left) vs. 2023 (right)

Catering to the specific needs of the hiking community is the easy part: I just have to listen. The hiking community asks the questions that I may or may not have asked myself. The difficult (and fun) part is creating answers for the community expressed in numerous iterations of web/print maps, data books, tables, and charts.

Let’s discuss your efforts to incorporate cloud-native geospatial technology into the development of your trail maps and applications. How did you discover these cloud-native tools, and what made you decide to leverage them for your projects?

In 2019(?), I read an article by Planet or someone at Planet on the subject of Cloud Optimized GeoTIFF (COG). The idea was certainly interesting and it found a place in a corner of my mind, but no action on my part. In 2021, I read a COG use case by Sean Rennie & Alasdair Hitchins that mentioned the use of a JavaScript API called georaster-layer-for-leaflet created by Daniel DuFour. This critical API is what I use today for COG in my Leaflet maps.

Some time later, I stumbled across an example showing 12GB of census block data being displayed on a Leaflet map. That blew my mind, which led to my investigation of the FlatGeobuf (FGB) vector format. This indexed vector data format uses the same underlying HTTP protocol streaming mechanism used by COG. Björn Harrtell is the big brain behind Flatgeobuf.

There are other cloud-native vector formats that many find useful, such as pmtiles. For the sake of simplicity, I settled solely on FGB. Should I need more from my cloud-native vector data, I may revisit that decision.

For me, the most compelling reason to utilize cloud-native tools/data is the ability of the client/web app to retrieve data directly from cloud storage (such as S3) using no intermediate server or services. This means no tile servers, databases, caches or resources to support these services. Imagine a fully functional Leaflet map with numerous vector/raster layers using only a web browser and cheap cloud storage!

Can you take us through the process of how you learned and familiarized yourself with these cloud-native tools? Were there any particular resources or experts that played a significant role in your learning journey?

Read the fine manual, right? Both Flatgeobuf and georaster-layer-for-leaflet API’s have fully functional examples and documentation. GDAL has notoriously good documentation for all of its supported formats and utilities. With that, it’s a matter of reading the documentation, studying those examples and through trial and error, adapting it to your own needs.

In the larger context of cloud-native and geo-spatial, when people like Even Rouault, Daniel DuFour, Paul Ramsey, Chris Holmes, Matthias Mohr, Howard Butler, et al, post on social media or mailing lists, I lean forward to listen. The geo-spatial community is fortunate to have so many smart/creative individuals. Oh, and what would any of us be without Google?

When met with a new spatial format or concept, my first stop is GDAL. Does GDAL recognize this format? Do the utilities accommodate this concept? If the answer is no, that immediately tells me the format/concept has not reached critical mass and maybe it never will. Being the first to introduce the newest tech or ’the next big thing’ into production is a big no-no. I want proven and tested technologies that will be around tomorrow.

Could you elaborate on how cloud-native geospatial technologies have contributed to optimizing the performance of your mapping applications, or if there have been any challenges in implementing them?

As mentioned, with cloud-native data you don’t need any back-end servers or services. You don’t need resources to maintain those services. Once I went all in on cloud-native, I removed from production a WMS/WFS/WMTS server using PostgreSQL/PostGIS, MapServer, MapCache running on a r5.large EC2 server with 400GB of disk storage. Removing the need to run that server was huge. While I maintain the same kind of environment for development, it was no longer needed in production.

In 2007, I created my first web maps using Google Maps API and continued to do so until I fully switched to cloud-native in June of 2023. Relying solely on open source is a big plus.

Much of my cloud-native COG/FGB data gets updated hourly, daily, etc, and you still need back-end resources to do so. However, it’s greatly simplified. All remote data sources are retrieved and processed using GDAL utilities wrapped in BaSH scripts and scheduled using cron. Currently, my web maps support 87 raster/vector layers.

The biggest challenge for me was the mental leap to actually commit to cloud only and rewriting everything. I literally had 15 years of Google Maps API and back-end OGC services running my web maps. It took 6 months of developing/testing/rewriting until I was comfortable making the switch. For those starting with a blank sheet, cloud-native is an easy choice.

As with any technological integration, challenges can arise. Have you encountered any specific obstacles while incorporating these cloud-native tools into your maps? And if so, we would love to hear about how you tackled them and any valuable lessons you gained from the experience.

Static vs dynamic content will be a primary consideration for how fully you commit to cloud. With purely cloud-native data, this can push any dynamic spatial analysis onto the web app/client. In a perfect world I think this is ideal, but not always practical.

For example, on femaFHZ.com, I display various peril/hazard layers. The user has the ability to double-click on the map and retrieve 14 different perils for that lat/lon. Using purely cloud-native data sources, the web app would make 14 different requests from 14 different COGs, then process/display the results. That is not ideal. Using server side, I have a virtual raster (VRT) that contains these 14 different COG’s. The user lat/lon is sent via a simple web service, the virtual raster is queried and all 14 results are sent back. It’s a single request/response and extremely fast.

Building upon your experience, do you have any advice or recommendations for other map developers who may be considering adopting cloud-native geospatial tools? What key insights would you share with them?

Thoughtful data creation. Perhaps you’re displaying building footprints for the entire state of Utah. Should every web client calculate the area of every polygon each time it accesses the data? Maybe it’s wise to add an ‘area’ attribute in each FGB feature to avoid so much repetitive client-side math. You could calculate the area of the polygon only when the user interacts with it. Your approach may vary when dealing with hundreds vs millions of features.

Should my layer be COG or FGB? It’s not necessarily one or the other – it can be both. Using the building footprint example, is it practical to display vector footprints at zoom level 12 on your Leaflet map? You can’t make out any detail at that zoom level. Maybe have 2 versions of the data, a low resolution raster for displaying at zoom level 1-13 and vector at zoom 14-20. This is the technique I use at femaFHZ.com to display FEMA flood hazard data and the building footprint example.

Caution with FGB. If the extent of your 10GB vector data is contained within your map viewport extent at, say, zoom level 4, the FGB API will gladly download it all and try to display it. Using a similar approach as above, with wildfire perimeters, I create a low resolution vector data set for use at low zoom levels and use the complete data set at high zoom levels.

It’s OK if you don’t use cloud-native data exclusively. Most of my base maps (OSM, Satellite, Topo, etc) are hosted and maintained by someone else (thank you, open source community!). These are likely large, high availability tile cache servers behind content delivery networks. Don’t reinvent the wheel unless you can build a better mousetrap!

Keep it simple. Use core open source technology such as (GDAL, SQL, QGIS, PostgreSQL/PostGIS, SQLite/Spatialite, STAC, Leaflet,OpenLayers). Have a good understanding of how to use your tools! That cool tech you’re emotionally attached to may not be supported tomorrow and it might not be the best tool for the job.

Beware of proprietary geo-spatial companies offering cloud-native solutions who lost sight of their mission many, many financial statements ago.

Before we conclude, is there anything else you would like to share with our audience about your journey, the evolution of geospatial mapping, or any exciting projects you have in the pipeline?

The topic of cloud-native data is incomplete without discussing STAC. When working with many high resolution COGs, it’s difficult to juggle so many rasters. STAC will allow you to easily identify COGs (meta data) from a collection of COGs (catalog) defined by a bounding box. STAC has become widely accepted by private and government organizations alike. It’s imperative we continue to promote STAC as it’s the perfect marriage with COG. Radiant Earth’s Github page is an excellent place to start for learning more about STAC.

FOSS GIS goes to great lengths to support open source endeavors. Fortunately, many private and government entities, large and small, step up financially to support these endeavors. Many (if not all) proprietary geo-spatial companies use open source software in their offerings. Because you operate within the bounds of the license doesn’t absolve you from the responsibility of supporting open source. It’s in everyone’s best interest to support open source!

Thank you Radiant Earth for allowing me to speak on such an important topic, that’s necessary for the future of geospatial data on the web.

Our blog is open source. You can suggest edits on GitHub.