Performance Explorations of GeoParquet (and DuckDB)

As I mentioned in my previous post, I recently put out my first open source Python project. I wouldn’t say I’m super proud of it, at least not yet, as it’s far from what I imagine it could be. It’s also kind of a weird mix of a very specific tool to better format the Google Open Buildings dataset, mixed in with benchmarking experiments for different ways to format that data. But it felt good to actually release it, and was awesome to immediately get help on the packaging. I wanted to use this post to share some of the interesting results working with different tools and formats.

Note: The following comparisons should not be considered true benchmarking. It’s just a reporting of experiments I did on my laptop, and it only tests writing to the formats, not reading from them. But anyone is welcome to use the same commands as I did, as I released the code I was using. Some day I hope to make a more dedicated performance comparison tool.

The core thing the library does is translate the Google Open Building CSV’s into better formats. For this step I just use the same S2 structure that Google had, so that they’re in faster & better formats to do more with. FlatGeobuf, which is ideal for making PMTiles with Tippecanoe due to its spatial index, and GeoParquet, which is compact and fast, are the primary formats I explored.

I initially used GeoPandas for the Google Open Buildings dataset v2, having heard great things about it and after ChatGPT suggested it. Usually I’d just reach for ogr2ogr, but I wanted to split all the multipolygons into single polygons and didn’t know how to do that (I also wanted to drop latitude and longitude columns and it was cool how easy that is with GeoPandas). During the processing of the data I got curious about the performance differences between various file formats. I started with 0e9_buildings.csv, a 498 megabyte csv file. It took 1 minute and 46.8 seconds with FlatGeobuf and 11.3 seconds with GeoParquet. So I decided to test with Shapefile and Geopackage output, in case FlatGeobuf is just slow.

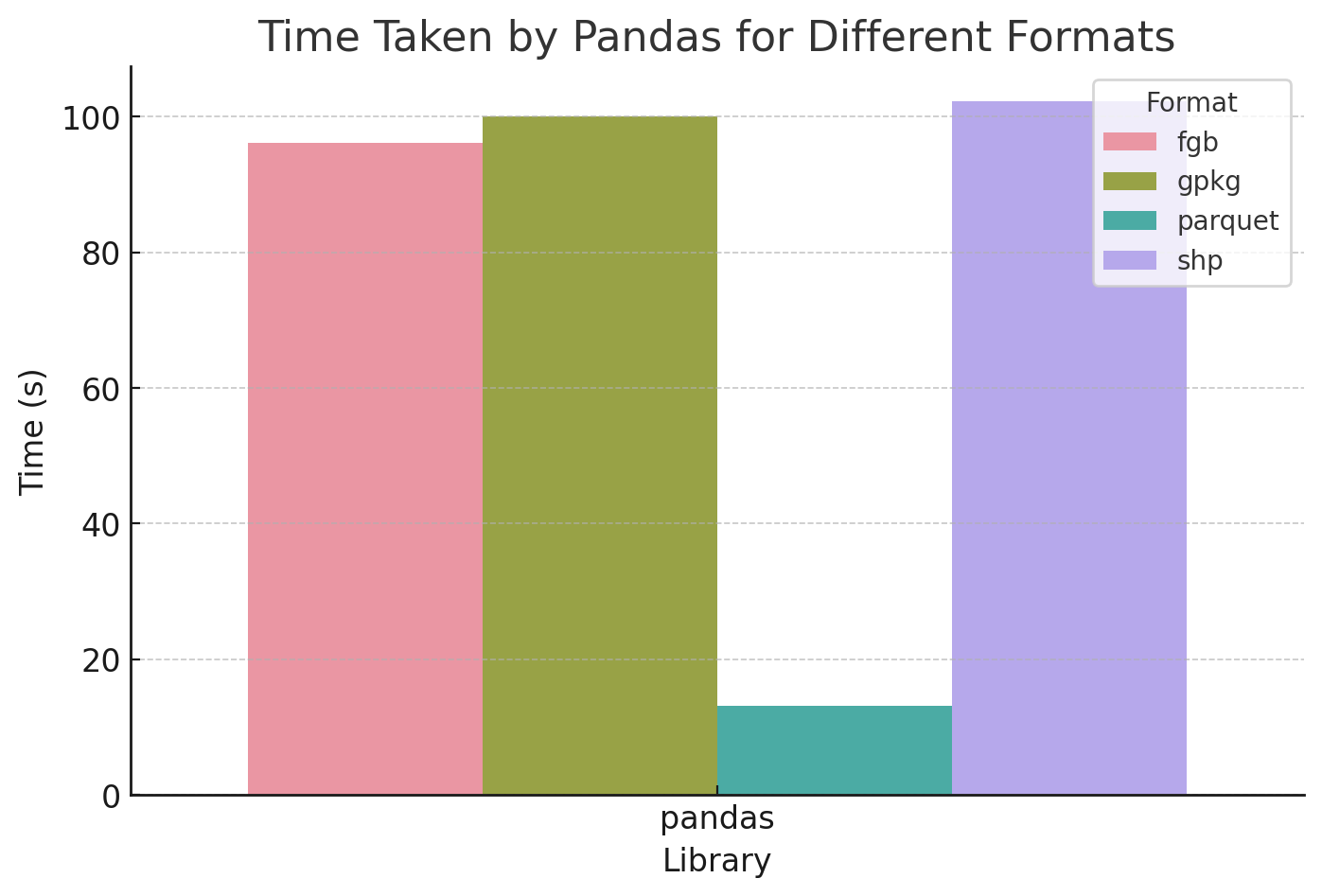

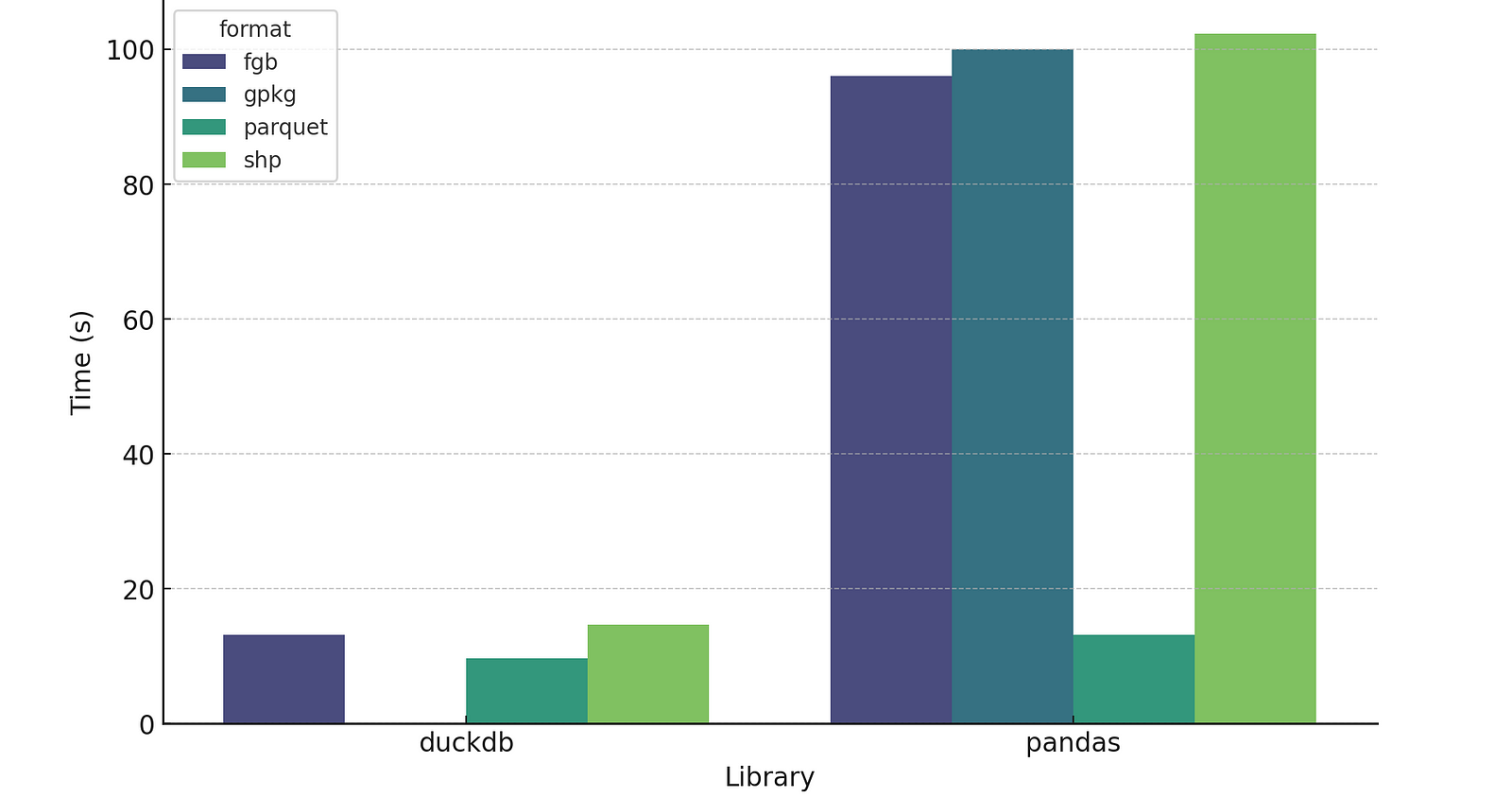

Comparing Pandas processing time for FlatGeobuf, Geopackage, Parquet, and Shapefile

Nope, FlatGeobuf is faster than either, with Geopackage taking 1 minute and 40 seconds and Shapefile 1 minute and 42.3 seconds.

File Size

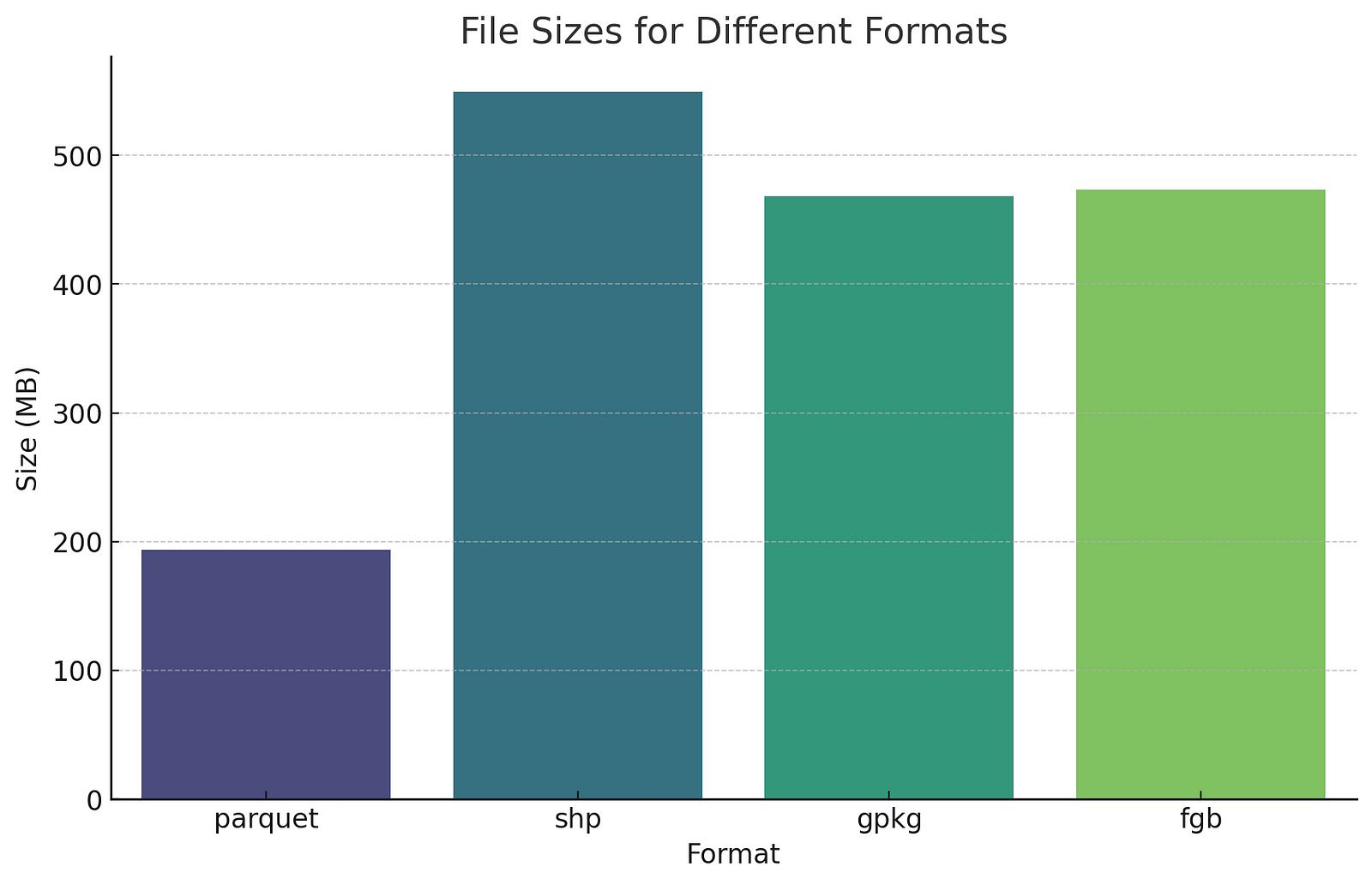

The other interesting thing was the size of the resulting files:

GeoPackage, Shapefile, and FlatGeobuf might not be much smaller than the CSV in terms of file size, but their spatial indices enhance performance in most use cases. You can also drag and drop into most any GIS system, while the CSV generally needs some intervention.

The chart above highlights another big benefit of GeoParquet – it’s substantially smaller than the other options. The reason for the difference is that Parquet is compressed by default. If you zip up the other formats they’re all about the same size as Parquet. But you typically have to unzip the files to actually work with them. Of course Even Rouault has changed the calculus with SOZip, which enables you to zip up traditional formats but still read them with GDAL/OGR. But with Parquet it’s really nice that you don’t have to think about it, the compression ‘just happens’, and you get much smaller files by default.

Note I didn’t include GeoJSON since I don’t think it’s appropriate for this use case. I love GeoJSON, and it’s one of my favorite formats, but its strength is web interchange – not large files storage and format conversion. But for those interested the GeoJSON version of the data is 807 megabytes.

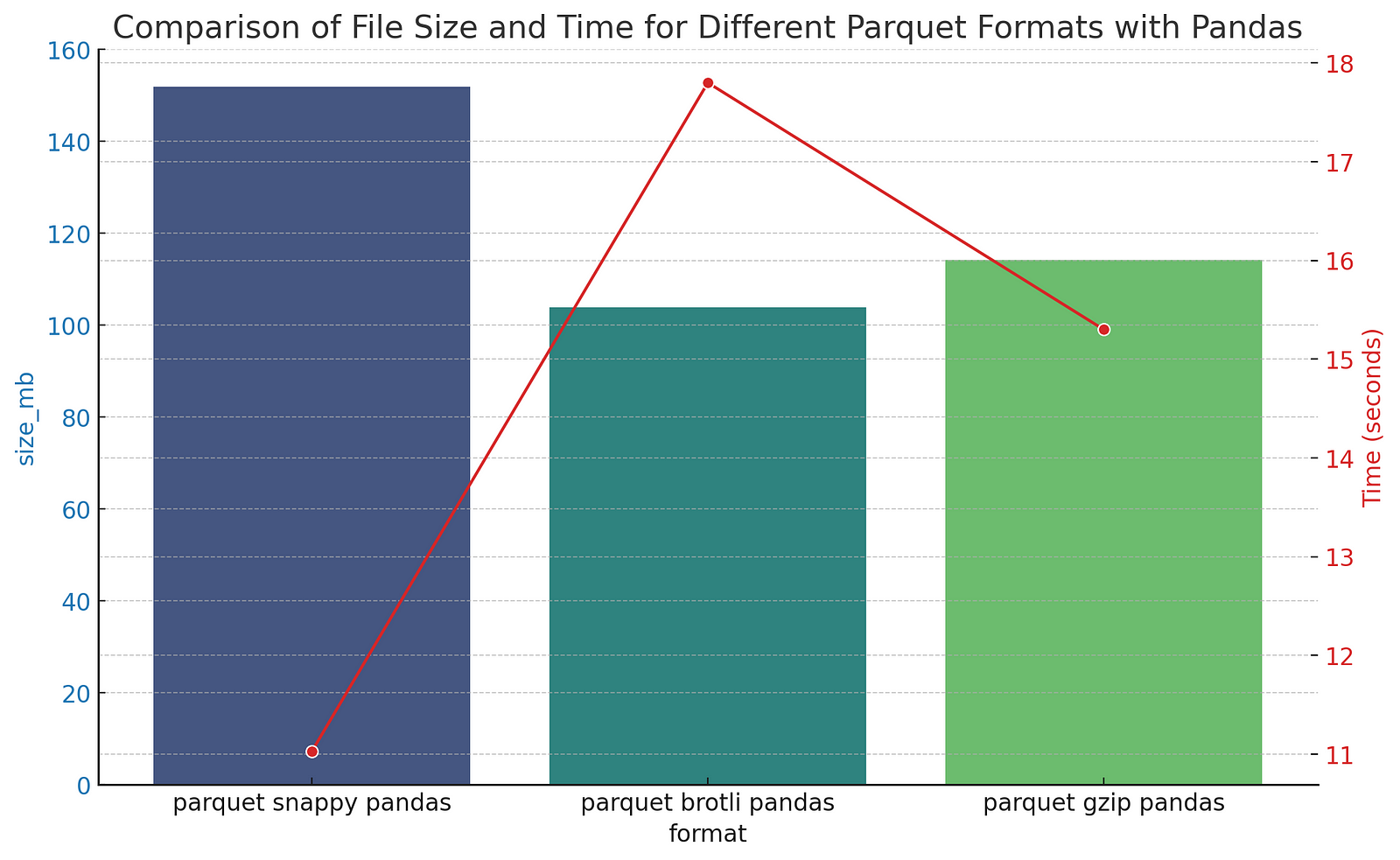

Parquet Compression Options

Even cooler, with Parquet you can select different types of compression. The default compression for most of the tools is ‘snappy’, which I’m pretty sure means that it optimizes speed of compression / decompression over absolute size. So I was curious to explore some of the trade-offs:

| Snappy | Brotli | GZIP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time (s) | 11.03 | 17.8 | 15.3 |

| Size (mb) | 151.9 | 103.8 | 114.2 |

The original CSV file was obviously smaller for this test, but it’s pretty cool that you can make the size 30% smaller (though it takes a bit longer). The one big caveat here is that not all the parquet tools in the geospatial ecosystem support all the compression options. DuckDB doesn’t support Brotli, for input or output, while GDAL/OGR does support it, but it depends on what compression the linked Arrow library was compiled with, so I wouldn’t actually recommend using Brotli (yet). But it’s great to see that mainstream innovation on compression gets incorporated directly into the format, and that all operations are done on the compressed data.

DuckDB

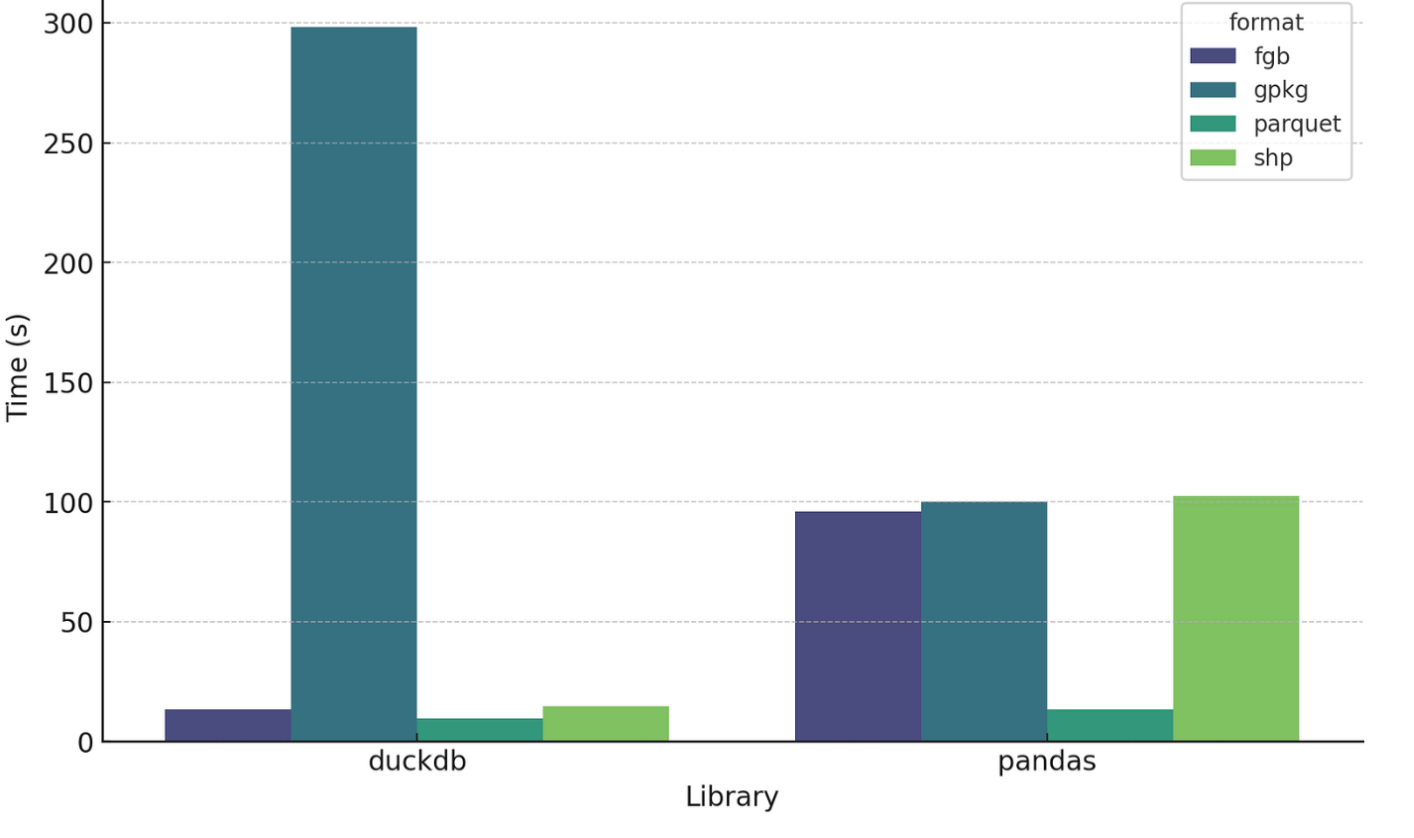

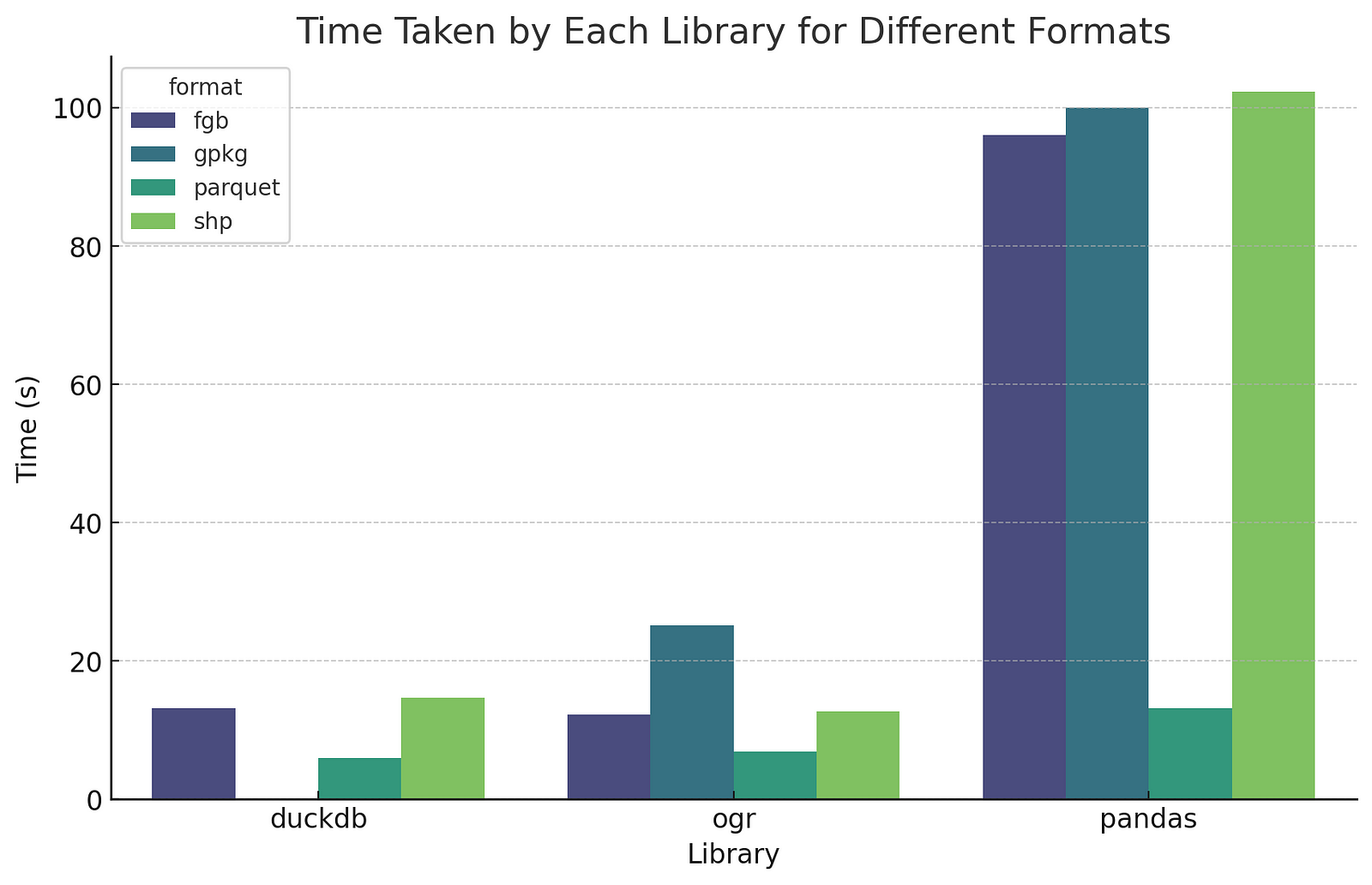

For processing v3 of the Google Buildings data I wanted to also try out using DuckDB directly as a processing engine, since with v2 the big files really pushed the memory of my machine and I suspected DuckDB might perform better. So I took the same files and built up the same processing steps (load CSV, remove latitude and longitude columns, split the multi-polygons), but in pure DuckDB. And the results were quite interesting:

Whoa! GeoPackage in DuckDB is super slow, but everything else is substantially faster (I suspect there’s a bug of some sort, but it is a consistent bug with any gpkg output of DuckDB).

Removing GeoPackage from the mix clarifies the comparison:

So DuckDB’s speed compared to Pandas for FlatGeobuf and Shapefile is quite impressive, and it is a bit faster for Parquet. One note is that these comparisons aren’t quite fair, as none of the DuckDB outputs are actually ‘correct’. Parquet output is not valid GeoParquet, since it doesn’t have the proper metadata, but it is a ‘compatible’ parquet file (WKB in lat/long w/ column named ‘geometry’), so the awesome GPQ is able to convert it. For this particular file the conversion adds 3.64 seconds, so even with the conversion it’s still faster than Pandas. And DuckDB should support native GeoParquet output at some point, and writing the proper metadata shouldn’t add any performance overhead, so the headline times will be real in the future.

FlatGeobuf and Shapefile output from DuckDB also need adjustment: the output does not actually have projection information in it. This is another one that I assume will be fixed before too long. In the meantime you can do an ogr2ogr post-process step, or add it on the fly when you open it in QGIS (it tends to ‘guess’ right and display, just has a little question mark by the layer and you can choose the right projection).

GDAL/OGR in the mix

I also got curious about how ogr2ogr compares, since DuckDB uses it under the hood for all its format support (except for Parquet). I just called it as a subprocess – a future iteration could compare calling the Python bindings or using Fiona. I did not take the time to figure out how I could split multipolygons with a pure ogr2ogr process (tips welcome!), and was mostly just interested in raw comparison times.

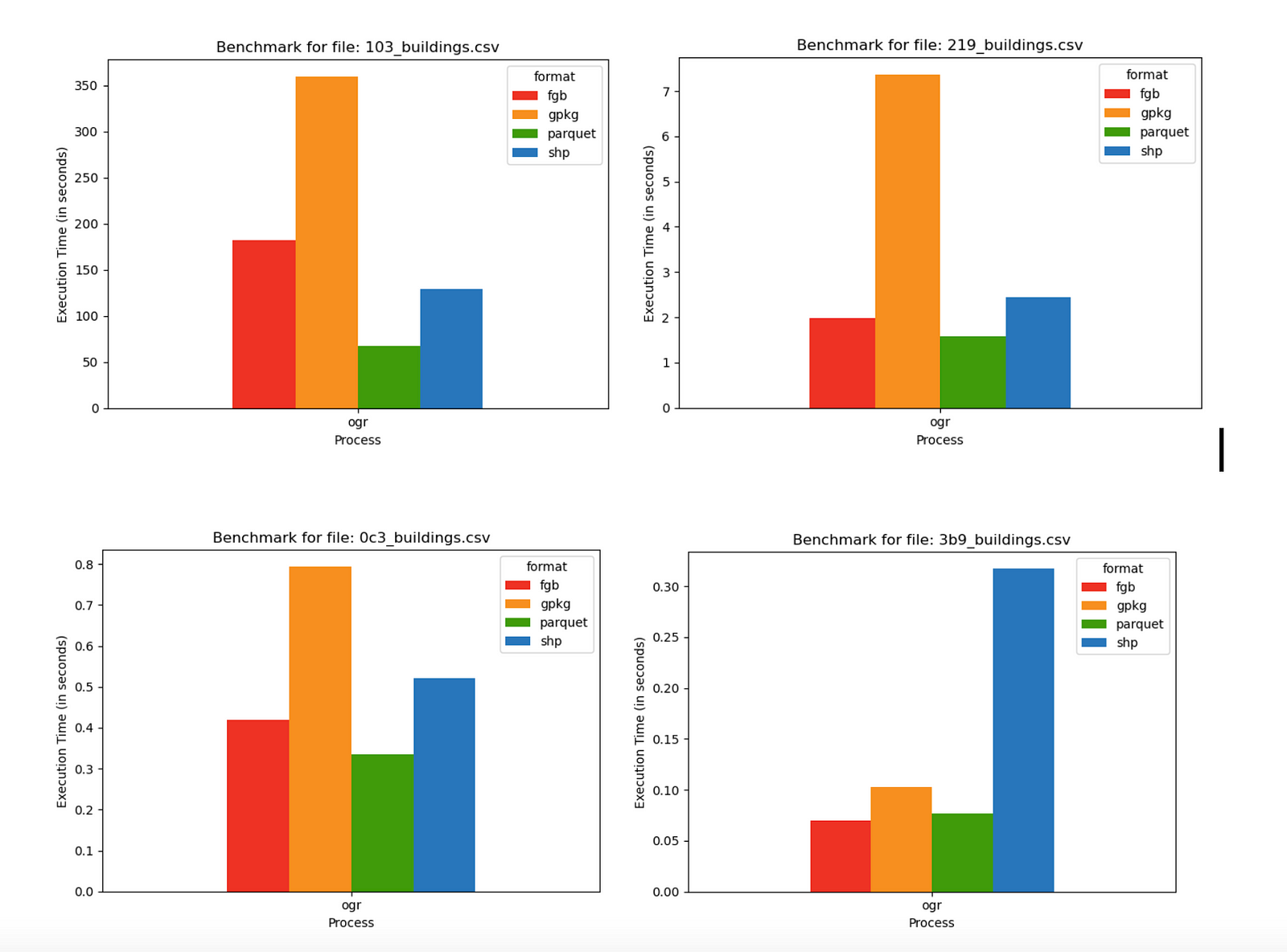

So DuckDB and OGR end up quite comparable, since DuckDB uses OGR under the hood. DuckDB is a little bit slower for GeoPackage and FlatGeobuf, which makes good sense as it’s doing a bit ‘more’. DuckDB’s pure Parquet output is faster since it isn’t using OGR (6.88 seconds with OGR, 5.97 with DuckDB), but as pointed out above right now it needs a GPQ post-processing step, which takes it to 9.61 seconds for fully valid GeoParquet output. Performance of different file sizes The other question I investigated a bit is whether the size of the file affects the relative performance much. So I tried with a 5.03 gb file (103_buildings), a 101 mb file (219_buildings), a 20.7 mb file (0c3_buildings) and a 1.1 mb file (3b6_buildings).

These were all done with ogr2ogr, since it gave the most consistent results. The relative performance was all quite comparable, except in the smallest file where FlatGeobuf edges out GeoParquet, and Shapefile takes a performance hit – but these times are all sub-second, so the difference isn’t going to make any real difference.

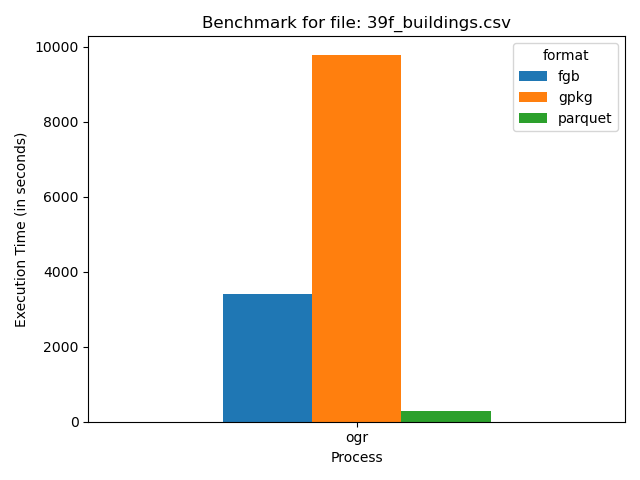

I also tried to compare all four on the largest CSV file in there, clocking in at 21.78 gb.

test

You may notice that Shapefile isn’t an option – that’s because it completely failed, highlighting why there are sites encouraging you to switch from Shapefile. First I got warnings that happened every time I did shapefile output – the column names get truncated since Shapefile can’t handle more than 10 characters in its field names. Then with larger files I’d get a number of warnings about the 2GB file size. But with ones over 10 gigabytes or so it would completely fail, reaching a maximum file size of ~4 gigabytes. So Shapefile is just not a good format for working with large amounts of data (I tend to avoid Shapefile as GeoPackage is better in most every way and now is almost as widely supported).

The performance of the other three was interesting. Parquet pulls ahead even more, processing the 21 gb in under 5 minutes and reducing its size to just 8.62 gb, while FlatGeobuf took just under an hour, and GeoPackage took over two and a half hours.

Try it yourself

As I mentioned above you are more than welcome to try out your own version of this testing. All the code I used is up at github.com/opengeos/open-buildings. You can just do pip install open-buildings and then from the command-line you can run open_buildings benchmark --help to see the options to put in. All the input needs to be Google Open Building CSV files downloaded from sites.research.google/open-buildings/#download.

I hope to spend some time refactoring the core benchmarking code to run against any input file, and also measure reading times, not just writing durations.

Conclusions

Like I mentioned in the warning above, this is far from rigorous benchmarking, it’s more a series of experiments, so I hesitate to draw any absolute conclusions about the speed of particular formats or processes. There may well be lots of situations where they perform more slowly. But for my particular use case, on my Mac laptop, GeoParquet is quite consistently faster and produces smaller output. And DuckDB has proven to be very promising in its speed and flexibility as a processing engine.

Once DuckDB manages to fix the highlighted set of issues it’s going to be a really compelling alternative in the geospatial world. My plan over the next few months is to use it for more processing of open buildings data – completing the cloud-native distribution of v3 of Google Open Buildings, and also using it to do a similar distribution of Overture (and ideally convincing them to adopt GeoParquet + partitioning by admin boundaries). I’ll aim to release all the code as open source, and if I have the time I’ll compare DuckDB to alternate approaches. I’m also working on a command-line tool to easily query and download these large buildings datasets, transforming them into any geospatial format, all using DuckDB. The initial results are promising after some tweaking, so hopefully I’ll publish that code and blog post soon too.

Our blog is open source. You can suggest edits on GitHub.