Cloud-Native Geospatial If You Don't Speak Snake

The Python ecosystem for open-source cloud-native geospatial tooling is fantastic. Projects like fsspec make it easy to work with cloud storage as if it were local, dask enables scaling computation from a single node to an entire server farm, libraries like zarr, kerchunk, and rasterio make it easy to read and write spatial data, which can then be analyzed with projects pandas and xarray.

But – and this might surprise a number of Python users! – some people don’t know Python, and some prefer to use other tools. Are those users simply out of luck?1

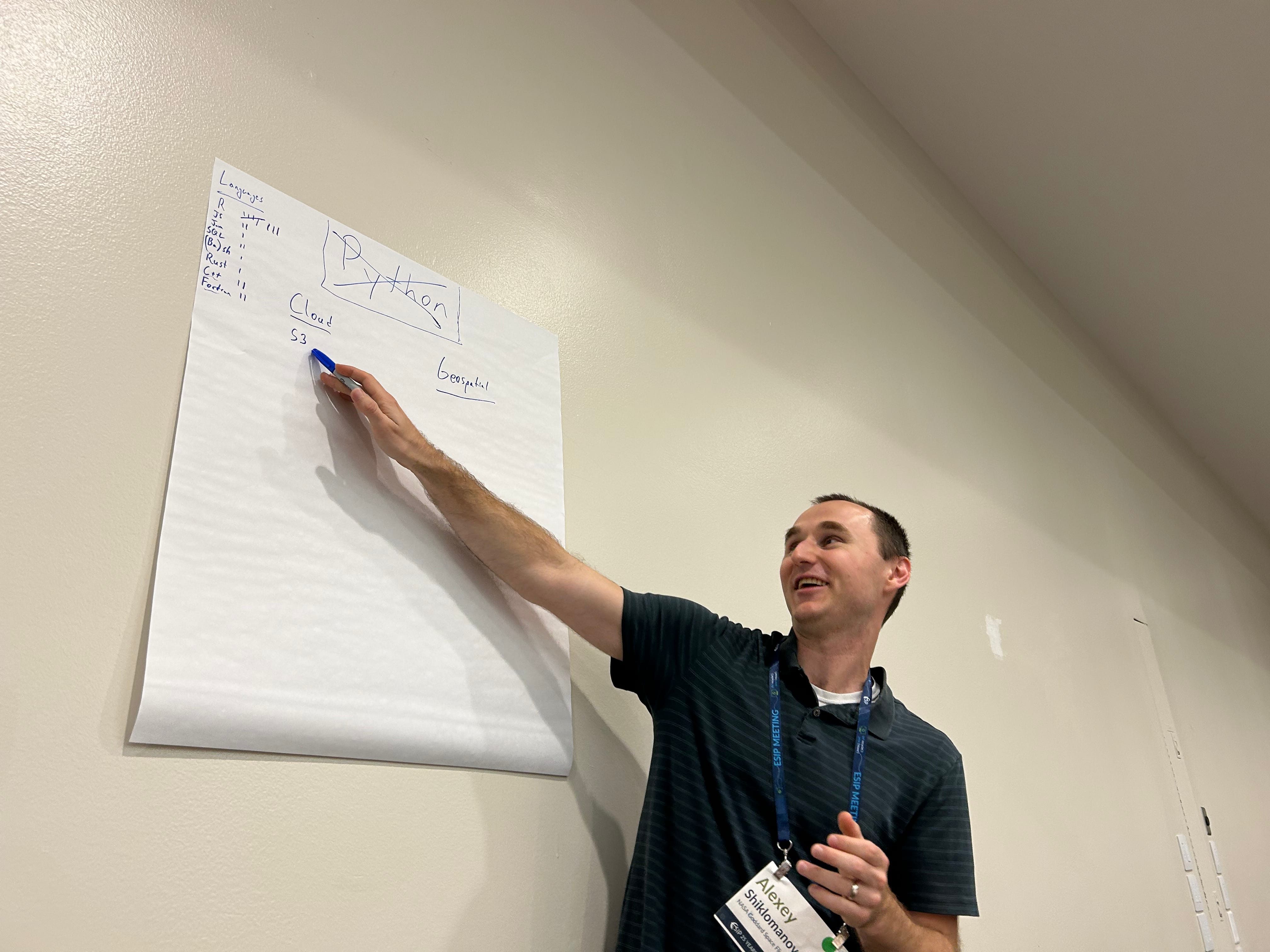

At the 2023 ESIP July Meeting, Alexey Shiklomanov organized an UnConference session around this very topic. We came away with quite a list of success stories of people using non-Python tools for cloud-native geospatial workflows, along with a few pain points that still need to be addressed to unlock the potential of other langauges for cloud-native geospatial workflows. Here’s a few of each.

Alexey Shiklomanov leading the Unconference session at the 2023 ESIP July Meeting.

Success stories

Perhaps the biggest surprise from the session is that there are many non-Python tools available for cloud-native geospatial workflows.

GDAL, PROJ, GEOS

The biggest open secret in spatial open source development is that huge chunks of most projects are fundamentally wrappers around three of the oldest spatial open-source libraries, namely GDAL, PROJ, and GEOS.

GDAL describes itself as a “translator library for raster and vector geospatial data”, making it easy to read and write spatial data in almost any format. GDAL’s virtual file system functionality is particularly useful for cloud-native workflows, letting users read data over network connections as if it were a local file.

PROJ meanwhile is a “generic coordinate transformation software”, providing standard translations between coordinate reference systems for cartographic and geodetic data. PROJ can be used to reproject spatial data directly, or indirectly via GDAL’s warping functionality.

Last but not least, GEOS is a library for “computational geometry with a focus on algorithms used in geographic information systems (GIS) software”, providing efficient algorithms for common spatial predicates and operations.

These core tools are highly optimized for reading, reprojecting, manipulating, and writing geospatial data, and work well in serverless environments and with data stored in cloud storage. Both PROJ and GDAL have useful command line interfaces, meaning they can be used directly in just about any cloud-native geospatial workflow without requiring a specific language runtime. It’s possible that most users of these libraries will never actually interact with the CLI, however; because GDAL, PROJ, and GEOS all provide C/C++ APIs, they can be wrapped into interfaces that allow users to take advantages of these libraries from other languages. For instance, GDAL has interfaces for Rust and Java and Python and more, allowing users in those languages to access these lower-level tools directly and build wrappers on top of their functionality.

Query engines

In addition to these core spatial libraries, there are a handful of language-agnostic tools that can help users analyze their data’s spatial and non-spatial attributes, similar to geopandas or xarray. Chief among these is PostGIS, a spatial extension to the venerable PostgreSQL database system that allows executing SQL queries against spatial databases from any language that supports ODBC interfaces. PostGIS can make it easy for users to access and analyze remote data sources by accepting queries and returning results over a network connection, making it useful for cloud-native workflows. However, as PostGIS uses a client/server architecture and requires setting up and administering a PostgreSQL server, it can often be too complex for users working on one-off analyses.

DuckDB’s Spatial extension is a very exciting new alternative to PostGIS, providing a spatial query engine without requiring a separate server process to execute queries. This extension uses GDAL to read spatial data in as tables, meaning your local DuckDB process can access files in cloud storage using GDAL’s virtual file system functionality, and is available either via the command line or via a huge number of language interfaces. While the extension still self-describes as a prototype, this query engine is a promising addition to the suite of language-agnostic tooling available for geospatial workflows.

Other low-level libraries

This is nowhere near an exhaustive list of language-agnostic geospatial tools available. There exist many more low-level libraries with interfaces to multiple languages, such as the s2geometry tool for geometric computations in geographic coordinate reference systems, or exactextract for fast zonal statistics. With more tools being released all the time, the future remains bright for language agnostic cloud-native geospatial workflows.

Remaining Challenges

That said, there are still challenges left in non-Python cloud-native geospatial workflows. I’m going to highlight two in particular: many useful tools don’t have low-level interfaces other languages can take advantage of, and many educational materials focus exclusively on the Python ecosystem.

Low-level libraries

First off, while a lot of useful tools do exist as low-level libraries that can be wrapped by other languages, a large number of tools in the Python spatial ecosystem don’t have any corresponding low-level utility that can be accessed without a Python runtime.2 There aren’t C/C++/Rust equivalents for dask, zarr, or xarray, and so workflows or tutorials that are written with these tools in mind are currently inaccessible to other languages.

If projects structure themselves by writing high-level wrappers around standalone low-level libraries, it’s relatively easy3 to add additional language interfaces to these tools as needed. But this is a lot of work, particularly given that most open-source projects start out as prototypes in higher-level languages with essential components moved to lower-level code over time as performance constraints demand. As such, many useful tools are currently locked-in to a single language ecosystem.

Education

Secondly, there’s a dearth of educational materials for non-Python users looking to tackle geospatial analysis projects. This is starting to change; in particular, there are many introductory books on using R for spatial analysis and data science, with more released every month. However, many specialized topics still only have official tutorials for Python users, and it would be useful for there to be more resources on using alternative tools for advanced spatial workflows.

Cloud-native geospatial in R

I’ve focused so far on language-agnostic tooling that have interfaces to multiple languages or the command line, as these tools are broadly useful no matter what language a user prefers working with. It’s worth spending some time looking at specifically the R ecosystem, however, as likely the next-largest language for geospatial workflows. R has a huge number of spatial libraries available,4 making it easy to download and wrangle spatial data. That said, there are some gaps in what R has available, and some challenges with what R does provide that makes a cloud-native workflow harder.

Things that work great

As I wrote last year, I absolutely love the core tooling available for working with spatial data in R. The sf package wraps GDAL, PROJ, and GEOS to provide a flexible and expressive vector toolkit, making it easy to read, manipulate, and write vector data from R and integrating naturally with dplyr and the rest of the R ecosystem for analysis workflows. The terra package provides a similar service for raster data, giving R users access to a highly-performant, fully-featured raster toolkit. Both of these packages rely on GDAL for their IO, meaning they can use GDAL’s virtual file system functionality to efficiently access cloud storage.

The objects returned by these packages integrate well with the ggplot2 ecosystem for cartography and data visualization, with a host of helper packages including tidyterra and ggspatial providing spatial-specific extensions. There are also a host of packages that focus on wrangling, analyzing, and modeling sf and terra objects, plus many more for accessing and downloading remote data sources.

Last but not least, the standard of documentation for R packages is incredibly high, with packages mandated to have standardized man pages explaining a function’s purpose, its arguments and return values, and providing helpful examples that get run as part of a package’s CI. These man pages are then often converted into beautiful bootstrap-based HTML documentation websites, courtesy of the pkgdown package. Many R users say that it’s the high caliber of documentation that got them to start using R, and that keeps them focused on the language.

Things that don’t

All that said, there are still some challenges with R’s spatial ecosystem.

First and foremost, none of the packages I just mentioned have standalone low-level libraries available for other languages to wrap. That means that some of the real strength of these libraries is locked within the R ecosystem. For instance, terra provides functions for focal statistics and averaging overlapping pixels when merging raster tiles,5 both of which are difficult to do using lower-level libraries. Right now, taking advantage of these functions requires an R runtime. Just to be extremely clear, I am not saying that anyone in particular should do the difficult work of extracting these components into lower-level libraries that multiple languages can wrap; I am however saying that doing so would be useful, if someone had interest or funding to do so.

Secondly, R is missing some of the “sugar” that makes it easy to write cloud-native Python code. There isn’t a perfect R equivalent to fsspec, meaning R users need to handle remote filesystems differently than they might local ones. While there are several parallelization backends available for R, these backends don’t scale to computer clusters and or task scheduling as easily as Dask. There’s still space in R for libraries that either wrap or re-implement some of these core workflow tools.

Third off, R packages are not often designed with serverless workflows in mind, and in particular often (due to CRAN requirements!) attempt to write and read from temporary directories that may or may not exist. This can require clever workarounds, or patches to the packages themselves to address.

And last but not least, as mentioned earlier, R users would benefit from more tutorials for advanced cloud-native workflows. This would be a fantastic place for the community – and funders – to invest in the near future, in order to help more users take advantage of cloud resources and improve their geospatial workflows going forward.

Our blog is open source. You can suggest edits on GitHub.