The Importance of Common Data Schemas and Identifiers

We created the Cloud-Native Geospatial Foundation because we’ve noticed rapid adoption of cloud-native geospatial formats, such as Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFF (COG), SpatioTemporal Asset Catalogs (STAC), Zarr, and GeoParquet. Both data providers and users enjoy time and cost savings when using cloud-native formats, and we believe there’s a need to help more people learn how to benefit from them.

Despite that, creating more cloud-native formats is a non-goal for us. There are plenty of people within our community working on cloud-native formats such as Cloud-Optimized Point Clouds (COPC), GeoZarr, and PMTiles. At this point, most use cases are covered by existing formats.1

In addition to the time and cost savings, one huge benefit of using cloud-native data formats is interoperability – the ability for different systems to share information easily. Common data formats are an essential part of interoperability, but we’re starting to explore a new dimension of data that is may be much more important to enabling interoperability: common data schemas and common identifiers.

This post is an effort to explain how common data schemas and identifiers can enable global cooperation and maximize the value of geospatial data.

The current state of schemas and identifiers in geospatial

Common data schemas refer to widely used ways to name and refer to the attributes and values within data products. Common identifiers are widely used ways to refer to unique entities in the world. To use a very simplistic example, a schema to describe a person could consist of first_name, last_name, passport_issuing_country, and passport_number. Because humans may share the same first and last names, we can’t use names as unique identifiers, but we can expect that countries will not issue the same passport number to multiple people. Therefore, a globally unique identifier for a person could be made up of a combination of the values of passport_issuing_country and passport_number.

While simple and imperfect in many ways, we have developed a several workable ways to describe and identify individual humans, which is foundational to things like travel, telecommunications, banking, and public safety. Let’s compare that to the present state of open geospatial data.

If you were to download parcel data from 3 different adjacent counties anywhere in the country today, the data you get would likely all have different names of attributes of those parcels. In Washington State, for example, King County shares data where parcel data is shared in a column named PIN, Pierce county parcels are in a column named parcel_num, and Snohomish county’s header is named PARCEL_ID. Likewise, each county uses different attributes with different names to describe those parcels. Because of this, if you wanted to combine the data into a single dataset containing parcels from different counties, you’d need to understand the meaning of each of their attributes and figure out how to translate them all to use consistent names.

Since parcel data is quite valuable, there are a number of companies who make it their business to acquire parcel data from official sources and transform it into a common data schema. At some level this makes sense – governments produce parcel data for their own local needs and have few incentives to spend time agreeing on schemas with other governments, and the market has found a way to solve the inefficiencies that come from this lack of coordination. But on another level, we think this this is something we should try to fix.

As we’ve written before, merely opening data is not enough. The current state of merely making geospatial data available for download does not amount to “infrastructure” if it fails to enable interoperability. Government agencies (and the citizens they serve) benefit when it’s easy for them to share data with their neighbors and other stakeholders. If we can lower the cost of consolidating disparate datasets, it will be easier for us to cooperate on shared challenges.

Cloud-Native Spatial Data Infrastructure

Because publishing cloud-native data is as simple as uploading files to a commodity cloud object service2, it is now easier for data publishers to collaborate and experiment with new schemas. This ease of experimentation was a major contributor to the development and adoption of STAC. Contrast this with the state of numerous open data portals today that require rigid data models and are designed in ways that discourage experimentation at the schema level.

One way to solve this problem could be to create a platform that requires data providers to use the same data model rather than having them build their own. We have a great example of a collaborative effort to do just that: OpenStreetmap (OSM). Just like Wikipedia provides a consistent format and is loosely governed by a set of principles to create one huge encyclopedia for the world, OSM has created a shared space for anyone to contribute to one huge map of the world. Despite the immense value created by OpenStreetMap, we believe that a better model for geospatial data beyond mapping data is the open source ecosystem.

Open source software doesn’t rely on one big repository with one set of rules governing one community. It’s incredibly diverse, made up of many different repositories, created by people with diverse needs, with different values embedded into their approach. Some projects are large and benefit from many contributors. Others are relatively small tools maintained by just a few people. Some projects are esoteric and others are foundational to the entire Internet. A robust cloud-native spatial data infrastructure can share a similar structure, emerging from contributions made by many communities that are cross-dependent with one another.

The way to enable collaboration across such a diverse community is by providing foundational datasets, identifying a few core identifiers and geometries that everyone relies upon, and providing flexible schemas that enable different communities to meet their unique needs while speaking a common language. From our perspective, enabling diversity isn’t merely a nice thing to have, but it’s core to maximizing the value of geospatial data.

Once a common data schema is established, everyone publishing data in that format is contributing towards a collective understanding of our world. That sounds grand, but it’s not impossible. It’s similar to how languages develop. To do this, we propose starting by focusing fundamental attributes of our environment that are easy to understand across different contexts.

We also don’t envision a single data schema that everyone has to align to. Instead, there’s a way to start with a small, common core of information that gives data providers the flexibility to use the pieces that are relevant to them and easily add their own. This approach is based on our experience building the SpatioTemporal Asset Catalog core and extensions approach.

Enabling new applications and AI

If successful, this will not only make things easier for users who want to combine a few sets of data, but will enable the creation of new types of software and data-driven applications. One of the pitfalls of traditional GIS tools is that many GIS users have been satisfied as long as their data looked ok on a map. We love maps, but a map is an interface created to deliver data to human eyes. If we want to maximize the value of geospatial data, it’s no longer enough to display it on maps – we need to optimize it for training AI models.

Common schemas and identifiers will make it much cheaper to write software that brings together diverse data, runs models, makes predictions, and lets people try out different scenarios. The approach we encourage enables data to remain fully abstracted, allowing software developers to point their code or models at it and have it “just work” without needing to be a data engineer.

A clear example of such innovative software is to create AI-based interfaces, and to realize the vision for ‘Queryable Earth’.

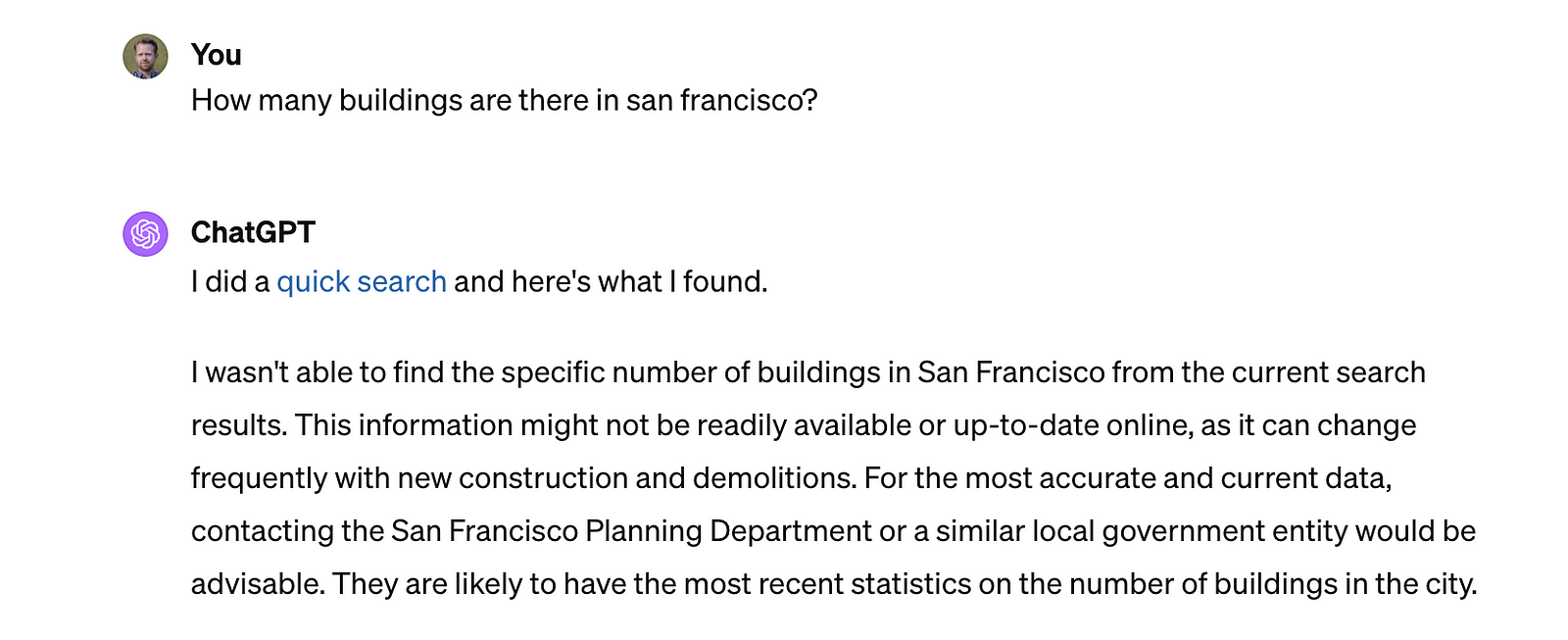

Right now, ChatGPT doesn’t know how many buildings there are in San Francisco, but this query is quite easy with a geographic information system, after downloading the building footprints dataset from data.sfgov.org.

Making geospatial data available in common schemas will make it easier for models like ChatGPT to answer questions about our environment, but it will also let us ask more challenging questions, like ‘How many buildings are there in San Francisco over 200 feet tall’? Or even ‘what percent of buildings in San Francisco are within 500 feet of a bus stop?’. These are questions that a common data schema makes possible and potentially even easy. The first question just needs a definition of ‘height’ in any building data set, and the second needs a definition of ‘bus stop’ datasets.

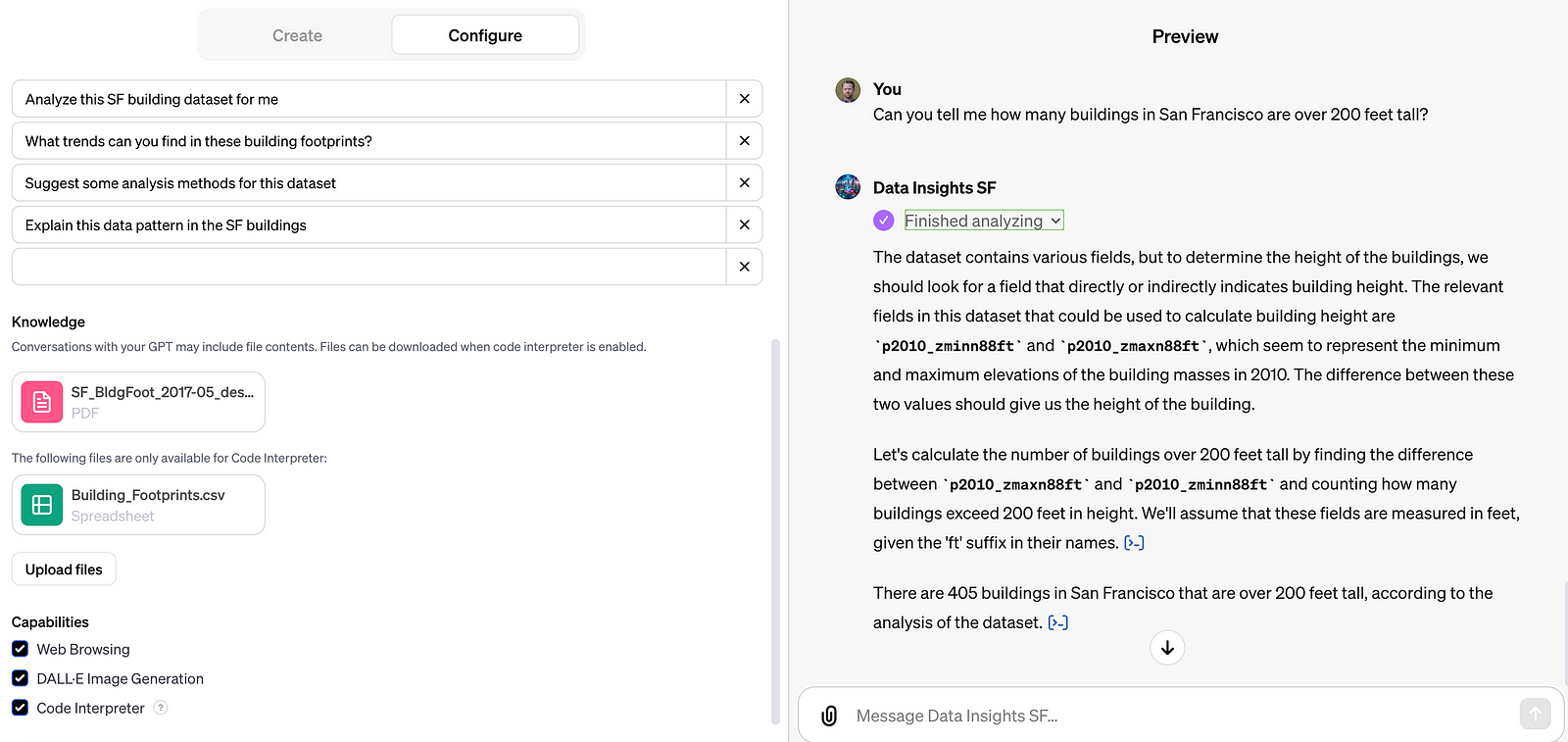

Thinking further, this approach would make it trivial to write a GPT that would work with any ‘building’ dataset, especially if the dataset used a data schema with well-defined fields.

The above is a GPT made with the San Francisco dataset to illustrate the point. Yes, the GPT provided an answer when asked about the number of buildings over 200 feet tall in San Francisco, but the answer is not actually right. The attribute it used for “feet” was actually a shortened name for P2010mass_ZmaxN88ft which is defined in the dataset’s PDF documentation as ‘Input building mass (of 2010,) maximum Z vertex elevation, NAVD 1988 ft’. ChatGPT couldn’t find where to get the height of buildings, so it used another column that shows the mass of buildings, calculated by LiDAR. There are actually at least 11 potential height values in this dataset. Part of the challenge of defining common schemas will be to identify and prioritize sensible defaults, so we can create simpler tools that provide the results that most people expect, while allowing extensions for people who have more specific queries.

Supporting climate use cases with common identifiers

This general pattern should work for any common type of data and creates opportunities to improve the usability of data for climate use cases. We can imagine common schemas used to describe land parcels, pollution, trees, demographics, waterways, ports, etc.3

In particular, we are already focusing on ways to enable interoperability of agricultural data, finding common schemas for things like farm field boundaries, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), leaf area index, soil water content, yield predictions, crop type, and more.

Varda’s Global FieldID

This is where the combination of common schemas and identifiers becomes powerful. We have been collaborating with Varda, a group that has created a collaborative approach to creating Global FieldID, a service creates stable, globally unique identifiers for farm field boundaries. By merely providing a common way to refer to farm fields, Global FieldID creates more transparent agricultural supply chains and simplify regulation to encourage regenerative agriculture practices and prevent deforestation. Beyond those benefits, having a common way to refer to farm fields will dramatically lower the cost of collaboration on agricultural data.

Other great examples of pioneering work to create global identifiers include Open Supply Hub which creates unique IDs for manufacturing sites, and the Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation which issues unique identifiers for legal entities all over the world.

A powerful benefit of common identifiers is how they allow different databases to refer to the same thing. A commonly used identifier can be used as a ‘join key’ that users can use to combine (or join) disparate datasets. This opens up a possibility to distribute information that’s spatial in nature, without having to always include geometry or location data.

For example, Planet provides data products that include Planetary Variables, like crop biomass and soil water content, that are updated daily. These data products are rasters, and many workflows involve downloading the full raster every day. But if we had a common schema and a common identifier for farm field boundaries, these variables could be easily summarized into a simple table that contains the variable value and the field ID. Rather than redundantly sharing or storing geometry data, users could just update soil water content as it relates to their field IDs each day.

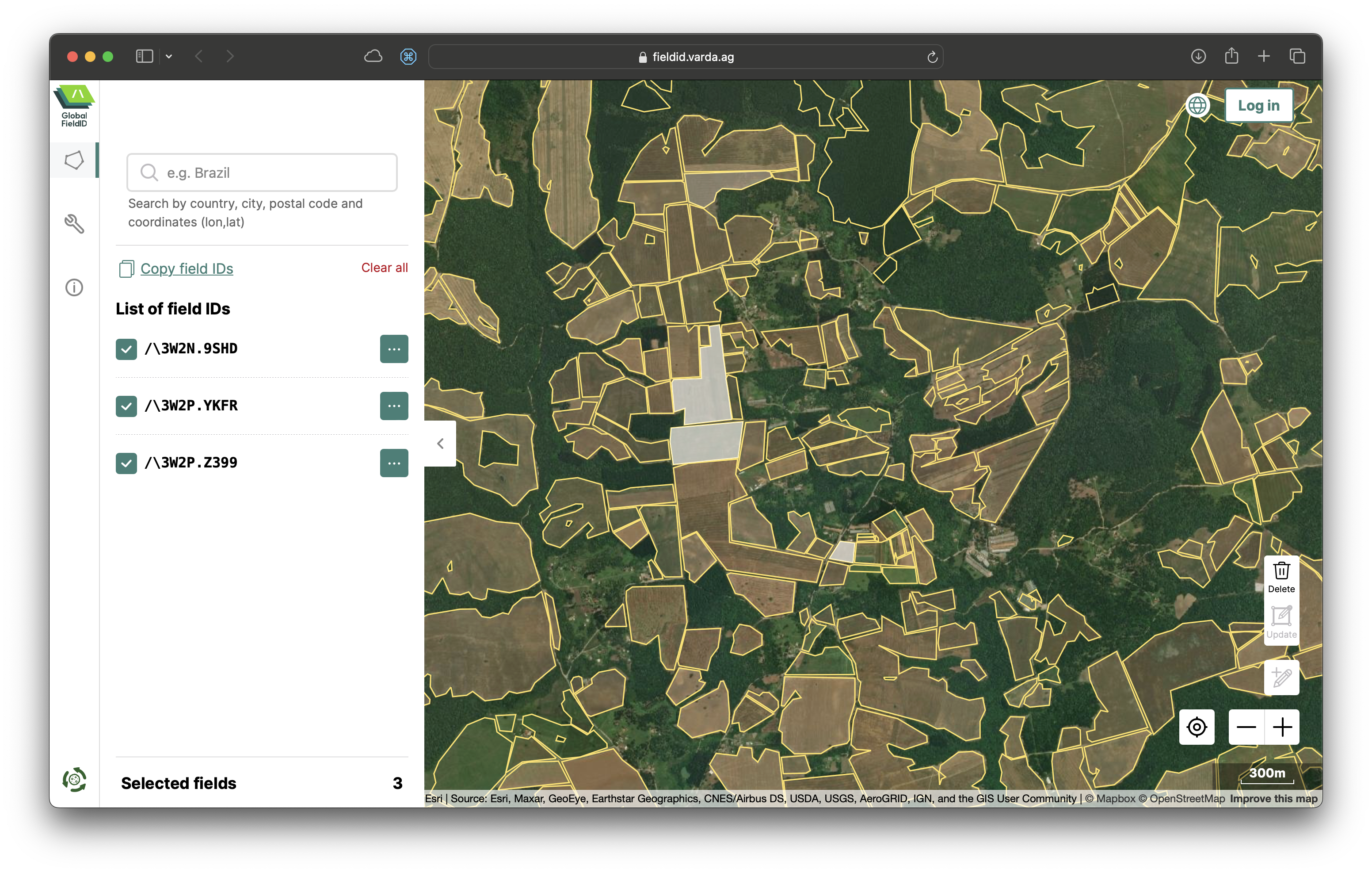

Screenshot taken from Varda’s Global FieldID service showing field boundaries and their identifiers in southern Brazil.

Taking this further, these common identifiers provide a shared framework for everyone to create all kinds of new agricultural data products that are interoperable with other systems. Imagine a Kenyan entrepreneur who has access to local data sources and insights that allow them to develop accurate yield predictions for maize in their region – common field boundary data and identifiers would allow them to create a data product that is as simple a table with predicted yield per field specified by the field’s ID.

Similarly, someone focused on exposure data for disaster risk assessment in supply chains could data from OpenSupplyHub and create a table that adds information about building materials and occupants to OpenSupplyHub production facility IDs.

Full communities could form around adding attributes to globally defined datasets. The GeoAsset Project could be streamlined by people collaborating globally to add ownership information to unique building identifiers in Overture, unique farm fields in Global FieldID, production facility IDs in OpenSupplyHub, or any find of asset that can be assigned a unique identifier.4 This would allow someone to create a GPT that could answer questions like “Which suppliers in our supply chain are most exposed to flood risk?” and “Are there any development groups who we could work with to mitigate flood risk where we operate?”

What’s next

We are going to be working out these ideas throughout the course of the year, diving deeper into use cases and showcasing examples of data products that put these ideas into practice on Source Cooperative.

We will specifically be working on issues related to air quality in collaboration with AWS and applying AI to agricultural data with the Taylor Geospatial Engine as part of their first Innovation Bridge program.

If you know of any good examples of common data schemas or groups working on creating common identifiers, we’d love to hear about them. Please write to us at hello@cloudnativegeo.org.

If you enjoyed this, please consider watching Chris Holmes’s presentation at FOSS4G-NA 2023: Towards a Cloud Native Spatial Data Infrastructure. Or you can just read the speaker notes in his slide deck.

This is not to say we believe the existing formats will live forever – we welcome more innovation in cloud-native formats and will support members of our community as they explore new formats. ↩︎

And we’re working hard to make hosting data in the cloud as easy as possible through Source Cooperative. ↩︎

We want to reiterate that we know none of this will be simple (n.b. these two great papers: When is a forest a forest? and When is a forest not a forest?), but we believe it is possible. ↩︎

The Radiant Earth post Unicorns, Show Ponies, and Gazelles argues that we need to create new kinds of organizations that can create and manage global unique identifiers to make this vision a reality. ↩︎

Our blog is open source. You can suggest edits on GitHub.