Towards Flexible Data Schemas

Following up on the importance of data schemas and ID’s blog post, I wanted to dig into the topic of data schemas. In the Cloud Native Spatial Data Infrastructure section, it posited that instead of a model like OpenStreetMap, where everyone contributes to a single database, a better inspiration might be open source software. This way of working wouldn’t require everyone to follow the same set of community and governance norms — it would encourage different approaches and more experimentation, and a wider variety of data types to collaborate around. That section closed with the thought:

We … don’t envision a single data schema that everyone has to align to. Instead, there’s a way to start with a small, common core of information that gives data providers the flexibility to use the pieces that are relevant to them and easily add their own.

I believe the foundation we’ve been laying with Cloud Native Geospatial formats has the potential to lead to much greater interoperability between data, if we can get a few things right. So, I wanted to use this post to explore how we can do things a bit differently and potentially get closer to that vision by building on these great new formats.

Flexible Schemas

The first thing that we can do differently than what came before is to flexibly combine different data schemas. The key is to move away from how the geospatial world has done things with XML, particularly the way validation works. In the XML world, you’d use an XML Schema to define how each field should work, and then the same XML Schema would validate if the fields in your document had the proper values. The big problem was that if an extra field was added, then the validation would fail. You could, of course, extend the XML Schema definition, but it it’s not easy to ‘mix and match’ — to just have a few different XML Schemas validate different parts of your data.

The cool thing is that with JSON Schema, you can easily do this. Six different JSON Schemas can all validate the same JSON file, each checking their particular part. And the situation is similar with Parquet & GeoParquet: there’s nothing that will break there either if the data has an extra column. We’ve used this to great effect in STAC — the core STAC spec only defines a few fields, and includes the JSON Schema to validate the core. But each ‘extension’ in STAC also has its own JSON Schema. Any STAC Validator will use each extension’s schema to validate the whole file.

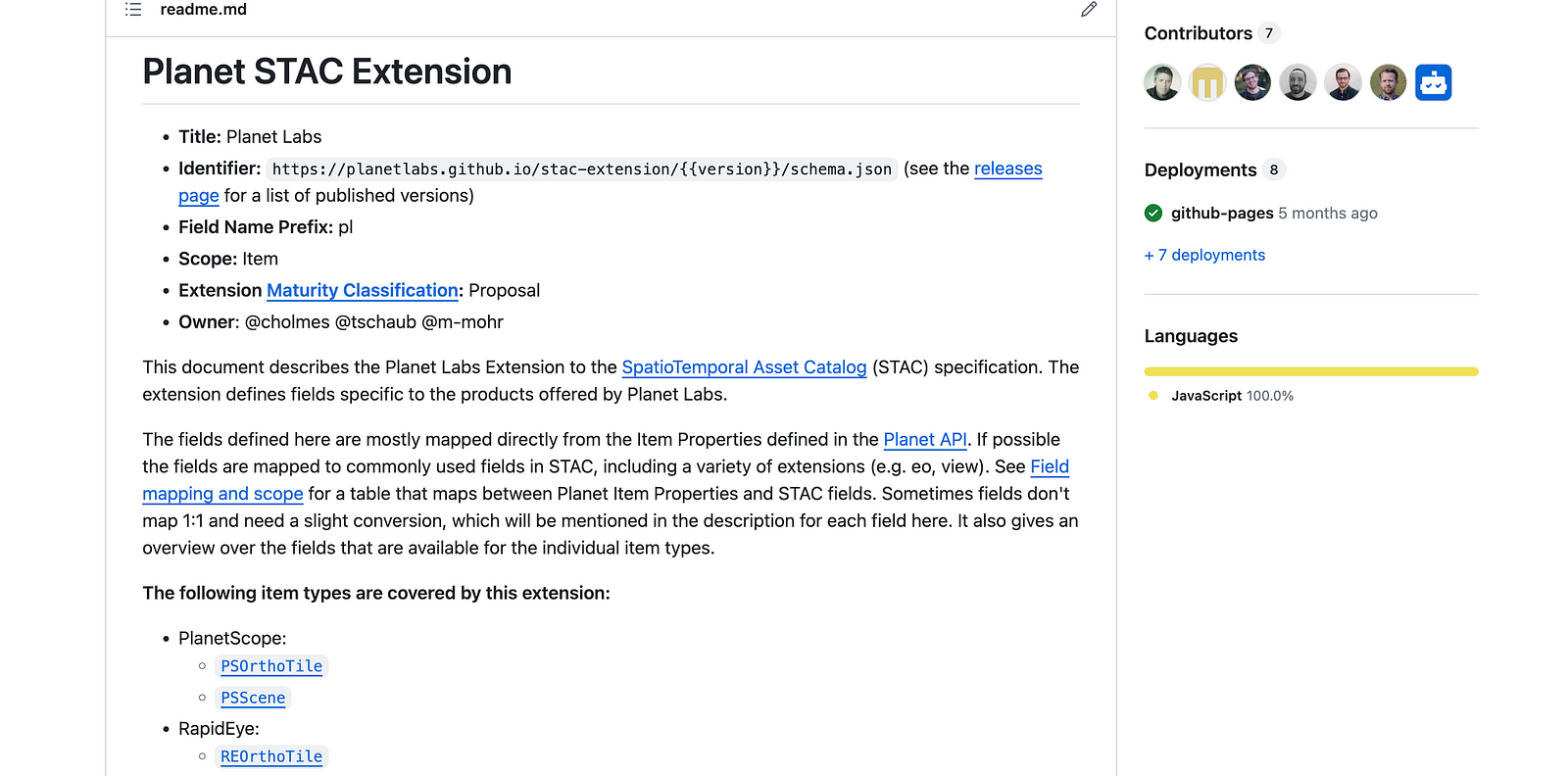

This has profound implications, since it enables a much more ‘bottom up’ approach to the evolution of the ‘data schema.’ In the XML world, you needed everyone to agree, and if someone disagreed they’d need to fork the XML Schema and redefine what they wanted. Users would then need to pick between which validation they wanted to use. So, it was really important that a top down entity set the standard. With the bottom up approach, anyone can define just a few fields for their own use, and others can define similar things in their own way. Of course, the core ‘thing,’ like SpatioTemporal Assets, needs to be done well. But I believe the key here is to make that core as simple as possible, so many extensions can thrive. Then, it’s just real world usage that decides which fields are important. And it also allows ‘incubation’ — a single organization can just decide to make their own validator for their fields. An example of this is Planet, with the Planet STAC Extension:

It uses a bunch of the common extensions like view, eo, proj and raster. And then it has some fields that are very specific to Planet’s system (item_type, strip_id, quality category), but there are a number of fields for which there is not yet a STAC extension. I say ‘yet’ because these are fields that are likely things that other satellites have for metadata, like clear_percent, ground_control and black_fill. They can be defined for Planet’s validation, since their users expect them. But others in the community can also look at Planet’s and decide to adopt what they did. And if a few different providers all do something similar, we can come together and agree on a common definition that we’ll all use. If two people decide to define the same ‘thing’ and both feel theirs is right, then both can exist, but likely one will gain more adoption and become the standard.

Global Datasets

One of my main observations from the last twenty years of working with standards is that having more data following the standard is the key to success. The best thought out specification that everyone agrees on will lose out to a poorly specified set way of doing things that has tons of data that everyone actually uses. This dynamic was clear with GML vs KML. The latter didn’t even have a formal specification for many years, but there was tons of data saved as KML. And the reason there was tons of data in KML in the first place is because it gave you access to an unprecedented amount of data in Google Earth for free — even if that data wasn’t itself available in KML.

So whatever dataset is the largest and most important in an ecosystem usually becomes the standard way of doing things, even if it didn’t set out to be ‘a standard’ — it becomes the defacto standard. Key to STAC’s success was that early on both Landsat and Sentinel 2 were available in the standard, and indeed it enabled those two major datasets to be more interoperable with each other.

With the explosion of satellite imagery and the continued advances in AI and computer vision we’re seeing more datasets that are truly global. The best of these will play a major role in setting the standard data schemas for whatever type of data they represent. Indeed I think we’ll see an interplay between aligning schemas for validated training data about foundational geospatial data types and the schemas of the resulting models. And hopefully, we’ll see major governmental data providers stepping up to the role they play in setting standards — a federal government defining a reusable schema for a particular domain, putting foundational data out in it, and also encouraging each state to use the same schema.

Overture Maps is doing really great work in building open global datasets for some of the most foundational geospatial layers, leveraging AI extensively. And they are taking their role in setting a data schema standard seriously, working to make it a flexible core that other attributes can be added to. I’m also excited to be working on fiboa as part of Taylor Geospatial Engine’s Field Boundary Initiative. It’s centered around the potential to use AI and Earth Observation data to build global datasets, and it’s doing some great innovation around the core data schemas to enable that.

Cloud-Native Geo Formats Require Deeper Alignment

I believe one of the main mistakes of past Spatial Data Infrastructure efforts was to try to punt on the hard problem of getting people to align their data. The message was that everyone could keep their database in its same schema, and the application servers delivering the API’s could just transform everything into standard schemas on the fly. This proved to be incredibly annoying to get right, as being able to map from anything to a complex data schema isn’t easy, and the tools to help do this well never really took off.

I think the fact that a Cloud-Native Spatial Data Infrastructure is fundamentally based on formats instead of API’s means that it will force people to confront the hard problem of actually aligning their data. We should be trying to get everyone actually using the same data schema in their day to day work, not just doing their internal work in one schema and transforming it into another schema to share it with others. It’ll be much easier if you share the buildings file from the city of Belém and its core attributes follow the same definitions as Overture. We shouldn’t have to go through data interchange servers (like Web Feature Services) just to share interoperable data: our goal needs to be making the actual data interoperable.

Obviously it’s unrealistic to expect everyone to just change their core database to a new schema. But it’s easier to use an ETL tool or a bit of code to actually transform the data and publish it than it is to set up a server and define an on the fly schema mapping against its database. And if we can get small core schema definitions with easy to use extensions then we won’t need to convince Belém to drop their schema and fully adopt ‘the standard’ — they should be able to update a couple core fields and define their own extensions that match their existing data schema, and slowly migrate to implementing more of the standard extensions.

Riding the Wave of Mainstream Data Innovation

The other thing we are starting to do is align with all the investment in mainstream data science and data engineering. One of the ways the founders would explain Planet in the early days was that they were leveraging the trillions of dollars of investment that has gone into the cell phone. Other satellites would buy parts that were ‘made for space,’ and were egregiously expensive because they were specially designed, with no economies of scale. Planet bought mostly off the shelf components, and was able to tap into the speed of innovation of the much bigger non-space world.

By embracing Parquet, we’re starting to do the same thing with geospatial. I think the comparison is apt — we’ve tended to build our own special stacks, reinventing how others do things. Open source geospatial software has been much better, like with PostGIS drafting off of PostgreSQL. But there is now huge investment going into lots of innovation around data.

In the context of data schemas, there are many people looking at data governance, and tools to define and validate data schemas. And so, we should be able to tap into a number of existing tools to do what we want with Parquet, instead of having to build all the tools from scratch.

Making it work

There’s some relatively easy things we can do to usher in an era of bottom-up innovation in data schemas. This should lead to much greater collaboration, and hopefully start a flywheel of Cloud-Native Spatial Data Infrastructure participation that will lead to a successful global SDI.

I think the key is to make it easy to create simple core schemas with easy to define extensions on top of the core. This mostly means creating a core toolset so anyone can create a schema, translate data into the schema, and validate any data against both that schema and its extensions.

The cool thing is that I think STAC has defined a really good way to do this, that just needs to be generalized and enhanced a bit.

Generalizing the STAC way

So STAC is ready to use if you want a data schema for data where the geometry is an indicator of the footprint of some other type of data, and there are links to the actual data. And then you can tap into all sorts of STAC extensions that help define additional parts of a flexible data schema. But if your data is like the vast majority of vector data, where the geometry and properties are the data, not metadata about some other data, then you can’t tap into all the great extensions and validation tools.

To generalize what STAC does, I believe we can build a construct that lets any type of vector data define a core JSON Schema and links to extensions. With STAC, you just look for stac_version and then you know that it can validate against the core STAC extension, and then stac_extensions is a list of links to the JSON schemas of the extensions it implements. The links are naturally versioned, as part of the URL of the schemas.

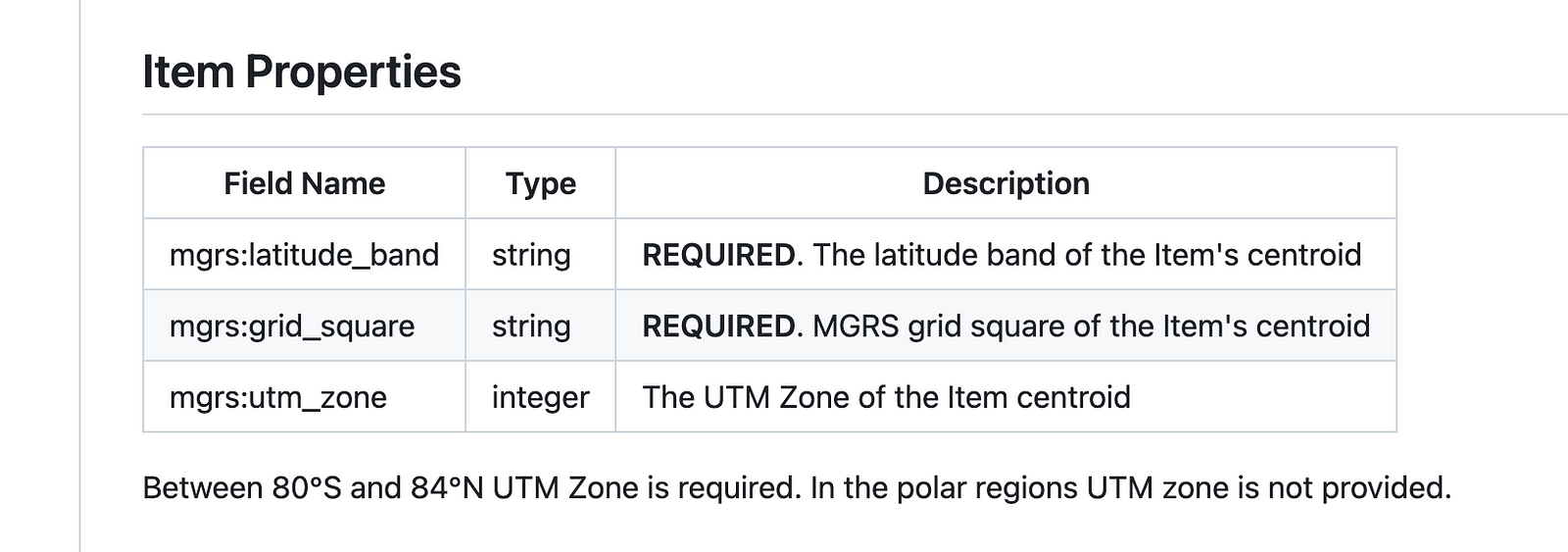

A general version could just have a definition that links to a single core schema (validating the geometry and any other attributes that are considered ‘core’). And then an extensions list that works the exact same way as STAC extensions. It perhaps could even directly use some STAC extension definitions like the MGRS extension, which could be used by any number of vector datasets that want to include MGRS:

Close readers will likely note that this approach would all unfortunately be incompatible with STAC, since STAC has hard coded versions. But I think if a wider ecosystem takes off in a big way we could consider a STAC 2.0 that fits properly into the hierarchy. And there’s probably some less elegant hacks you could do to make it all work together if that was needed.

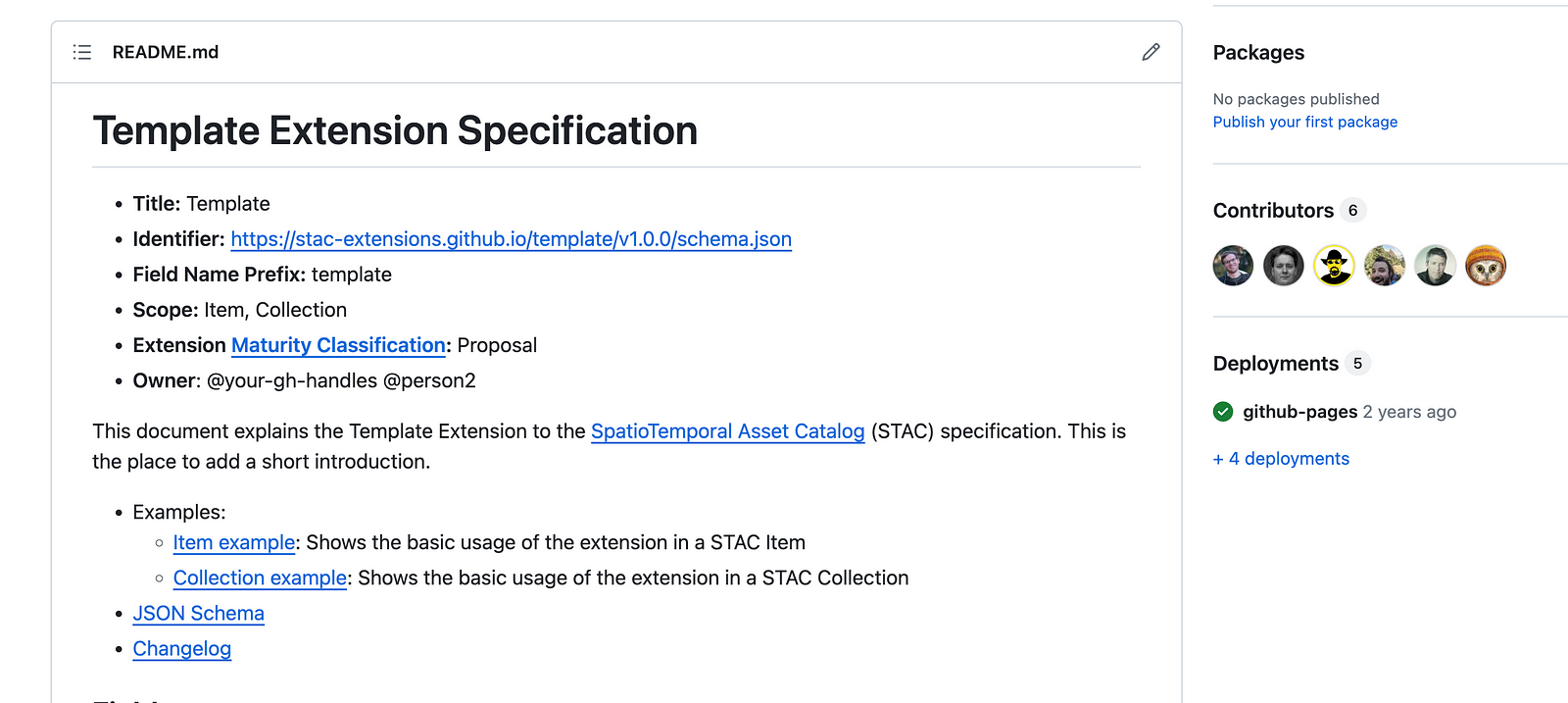

The other bit that would make a ton of sense to generalize is the STAC extension repository template. This to me is one of the most clever parts of the STAC ecosystem, and it’s all thanks to Matthias Mohr.

The core is it gives you a clear set of guidelines to fill out your own extension. You don’t need to check 3 other extensions to see how they do it, you just change the right places for yours and it then ‘fits’ with the ecosystem. But it goes far beyond that, as it clones a set of continuous integration tools. It will automatically check your markdown formatting, and once you finish your JSON Schema it will also check that all your examples conform to STAC and your defined extension.

And then when you publish a release it will automatically publish the JSON Schema in your repo on github pages, to be the official link. STAC validators can then immediately make use of it. So to create any new version of your extension you just need to cut a release. I hadn’t even known that anything like this was possible, but it made it such a breeze to create a new extension. You can focus on your data model, and not on how to release it and integrate into tooling, since it all ‘just works.’

Astute readers will realize that the recently announced fiboa project has explored a number of these ideas. It is a vector dataset focused on field boundaries, and it defined a small core and flexible extensions; Matthias adapted the STAC extension template concepts to a fiboa extension template. We have yet to go all the way to a ‘definition’ schema defined by a link to the core schema, as it felt like too much complexity for the first version, but if others start to do similar things we could do so by 1.0.

Enhancing the STAC schema toolset

So I think there’s a few ways we’d ideally go beyond just generalizing how STAC does things. The first one is to be compatible with GeoParquet. GeoParquet is a much more naturally default format for vector data on the cloud than GeoJSON is, and its support of different projections also will help support a wider variety of use cases. GeoJSON worked well for STAC, particularly because we had both the static STAC and the STAC API options. I originally imagined that large data sets would naturally be stored in a database and use a server that clients would query. But the fully cloud native approach has been quite appealing, and a number of very large datasets are just on object stores, and consist of millions of individual JSON files (next to the actual data files).

We’ve recently started to standardize on how to represent a full STAC collection in GeoParquet with the STAC GeoParquet Spec. I’ll hold off on a deep dive on that, but it’s pretty cool to be able to just query the entire STAC catalog without needing an API.

So for non-’asset’ data, where the geometries and properties are the data, not metadata, GeoParquet makes much more sense than GeoJSON as the main distribution format. But my hunch is that it likely will still make sense to define data schemas in more human readable formats. There is some argument for defining the core schemas completely abstractly, in something like UML, since formats will continue to change and we should be adaptable to that. But from my experience that introduces an unnecessary layer of abstraction. With STAC I actually started a SpatioTemporal Asset Metadata (STAM) spec, see https://github.com/radiantearth/stam-spec, to try to make abstract definitions that could map to JSON but also other formats (like GeoParquet though it didn’t exist yet, or as Tiff tags in a GeoTIFF). But it was a pain to try to maintain both and just didn’t add much.

fiboa Schema

For fiboa, Matthias defined something a bit less abstract than UML, defining a human-readable YAML-based language to describe the attributes and constraints and named fiboa Schema for now. Pure JSON schema didn’t quite work, since JSON has a limited number of types, so it couldn’t precisely describe the different data types commonly found in file formats such as GeoPackage and GeoParquet. Our intention is also that users create extensions, which need a separate schema definition for the added properties. As such the language is much simpler to lower the entry barrier for newcomer as we found in STAC and other projects that JSON Schema is too difficult for many. Nevertheless, the language is based on JSON Schema so it can easily be converted to valid JSON Schema. We’re not sure if it’s the right answer for all time, but it is working pretty well as a way to easily define schema information and have it validate in both JSON Schema and Parquet.

Overture is also using JSON Schema to define their schemas, so it’s nice they’re thinking in similar directions. Nevertheless, they’ve also identified the data type limitations that we’ve seen. For example, temporal information are stored in strings instead of native temporal data types and numerical types always use the biggest container (e.g. int32 instead of uint8). They say the final format for Overture deliveries hasn’t been set yet, but the most recent releases were GeoParquet. They also recently embraced snake_case for their naming, which is a minor detail, but does make it easier to potentially share extensions between the projects. My hope if that we can get to some common tools that let projects define schemas for vector data with properties across various file formats such as GeoParquet in human readable formats and get automatic validation tools. We are also experimenting and discussing with other related projects such as Overture to get feedback on our approach to make it general enough for other use cases.

Measuring Success

One final idea to generalize and hopefully really enhance is STAC Index. STAC Index provides a list of all public STAC Catalogs, and you can use a STAC Browser to easily browse the full extent of any of them. One of the original ideas of STAC Index was to crawl all the catalogs and provide lots of interesting stats on them. Tim Schaub built a crawler to do this and reported on the results in the State of STAC blog post, but ideally it would be a continuous crawling and reporting of stats.

I believe the key to a Cloud-Native Spatial Data Infrastructure is to make it really easy to measure how successful adoption has been. Not just counting the total of number of GeoParquet datasets, but to to track more details to be able to get some real nuance. Things like number of rows in GeoParquet, stats by particular data schemas (like fiboa), global spatial data coverage by data type, etc. There is a chance we’ll still use STAC, but likely just at the ‘collection’ level, to provide metadata on GeoParquet files. Though that’s something we’re still figuring out in fiboa — if we should adopt STAC Collection directly or just aim to be compatible with it — the latter feels a bit simpler.

So STAC Index should be enhanced to really be the ‘Cloud-Native SDI Index’, and serve as a clear KPI and scoreboard to really measure adoption. I should probably spend a whole blog post on the topic of measuring standard adoption at some point, as I have a suspicion that making it really easy to measure the actual adoption is a powerful lever to drive adoption.

Let’s do this!

So for me the next major project is to work on flexible schemas for foundational data sets. One obvious one is buildings, and Overture is doing incredible work there. They’re truly crushing it on figuring out a core, flexible data schema with global ideas, but I think it’d be awesome to build on what they’re doing in two ways. The first is to try to build validation tooling, and experiment with making other building datasets ‘overture compatible’. And the second would be to try out ‘extending’ their core schema with some additional fields. Perhaps something like building color, or roof type. I suppose the ideal would be to find some better attributed building dataset and make it Overture compatible — try to conflate the geometries, merge the common attributes, and make a schema for the extended attributes.

And then in fiboa we’re taking a serious run at defining flexible schemas for field boundaries and ag related data. If you’ve got interest in that then please join us! And if you’re interested in a different domain than buildings and field boundaries then don’t hesitate to take these ideas and run with them. And I just talked to a group about doing the same approach for forest data, so if you’re interested in collaborating on that let me know.We don’t have any explicit channel on the Cloud Native Geo slack, but I’m sure we can start on #geoparquet or #general and then spin one up.

Awhile ago on twitter I read this cool post on sub-national GDP.

This does seem like another opportunity — use Overture locality schema for sub-national boundaries at the core but add an attribute for GDP and other economic stats, and harmonize all the datasets listed.

I’d also love to hear of other opportunities for collaborations on data schemas, and other success stories where there are interoperable data standards, particular in domains that are further afield. I think it’d be interesting to try to adapt some of the successful ones into cloud-native formats, just to see if it works and if it adds value. So if anyone wants to work on that don’t hesitate to get in touch.

Our blog is open source. You can suggest edits on GitHub.